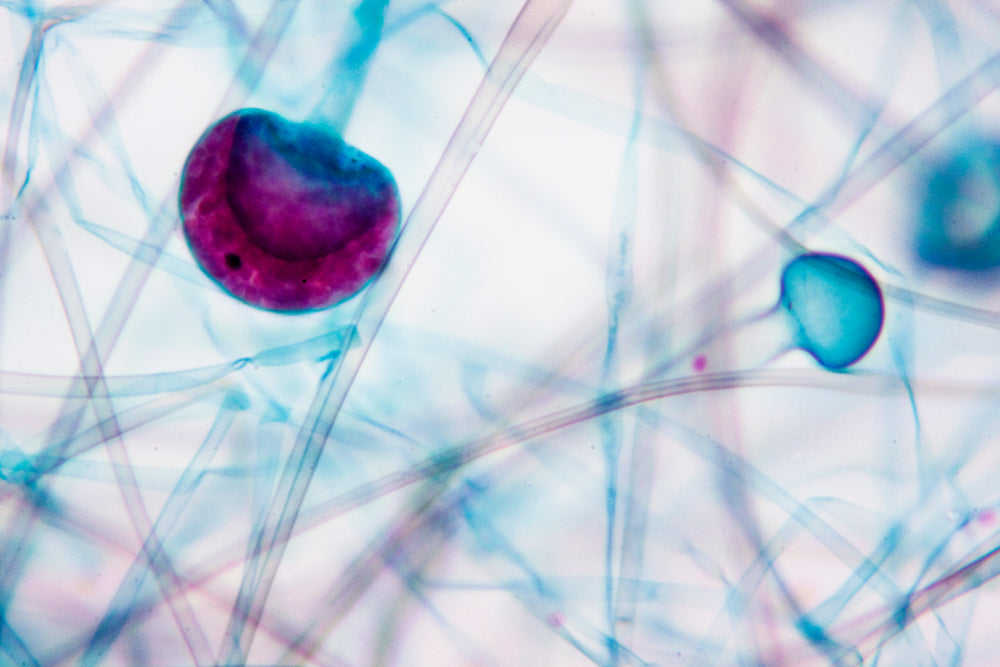

Much of the research on the gut microbiome has focused on its biggest component, the bacteria that inhabit the human intestine. However, the intestine is home to other microorganisms as well, including fungi. Of late, the human fungal communities that comprise our “MYCObiome” are finding their place in the research spotlight.

New research suggests that studying the mycobiome, and how it interacts with the bacterial component, can offer more clues in the development of chronic inflammatory diseases that affect the gastrointestinal system. For instance, Crohn’s Disease (CD) patients tend to have higher numbers of not just two bacteria, E. coli, and S. marcescens, but also a troublesome fungus, Candida tropicalis. The scientists also demonstrated that these three organisms, in collaboration, grow “out of control” and generate robust biofilms that can significantly worsen inflammation in the intestine.

The mycobiome and development of disease states

The role of the mycobiome in host health and the development of diseases may well be a significant one. Even though the mycobiome is a minority compared to the bacterial component, fungal cells are typically much larger in size and volume. The fungal biomass is actively interacting with the bacterial one, generating metabolites that may affect the gut bacteria and other systems. Intestinal fungi are also exposed to the same environmental factors, the same dietary intake, and so on as gut bacteria. They are capable of metabolizing nutrients to produce physiologically active molecules. Structurally speaking, fungi also bear surface antigens such as beta-glucan or mannans that are capable of crosstalk with the host’s immune system. This makes the mycobiome a player to be reckoned with.

The mycobiota composition is believed to be influenced by:

- Our diet (particularly, through fruit/vegetable fungal contamination or certain types of cheese)

- The variety of biochemically active molecules produced or secreted within the gut, such as peptides or bile acids

- Other microorganisms that live in the gut

The intestinal mycobiome is also likely to be influenced by the oral mycobiome, i.e., the fungi that live in our mouth cavity. Because of the direct anatomical link between the mouth and the gut, and by association, between what we eat and what ends up in our bowel, oral fungi will influence fungal colonization in the gut.

Next-generation sequencing data has cause to suggest that giving inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients antifungal drugs, in addition to a probiotic-rich in beneficial fungi like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, could be a potential therapeutic intervention. Targeting both the pathogenic bacterial component and the fungal component that supports the development or worsening of disease states may help reduce chronic intestinal inflammation. Antifungals and probiotics could also present a novel and complementary strategy to alleviate the side effects of current treatments, such as monoclonal antibodies, in the case of IBD. It could also help in restoring a healthy balance of “good” microorganisms.

At this point, further studies that include larger sample sizes are warranted to better understand all these interplays and identify novel and specific therapeutic targets.